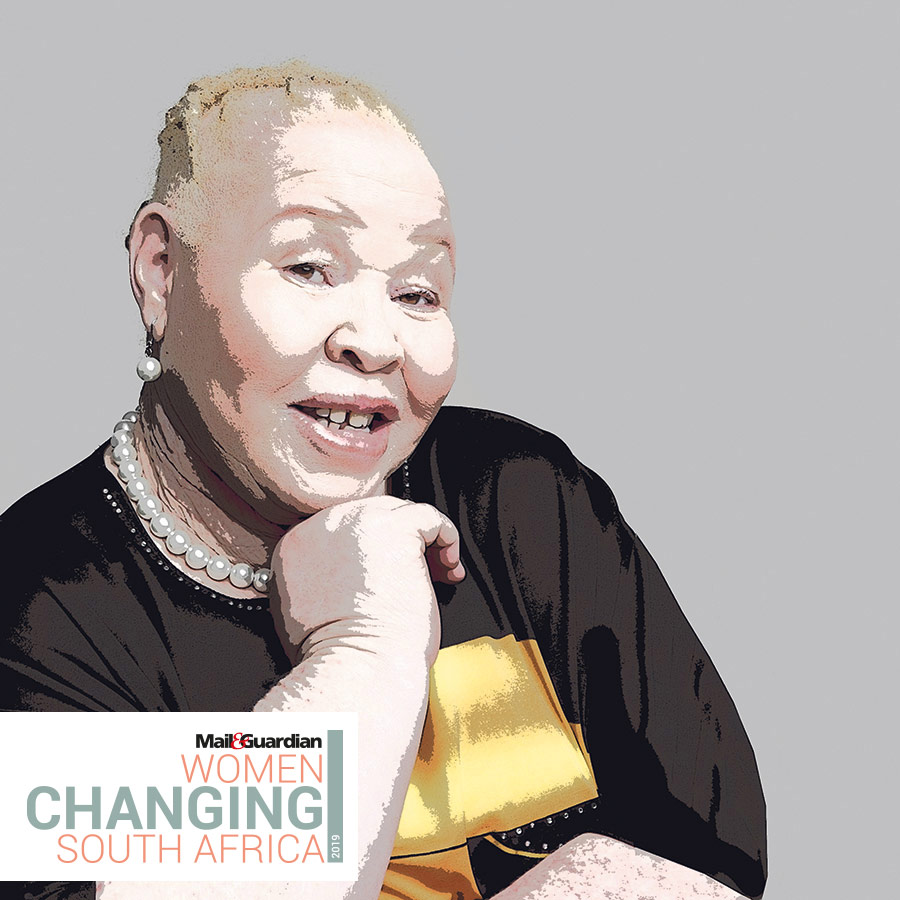

Nomasonto Mazibuko is no stranger to feeling like an outsider. She was born in Sophiatown and her family was among those removed by the apartheid regime to be settled in Meadowlands, Soweto, deemed to be far away enough from Johannesburg for black people. As one of 10 siblings, five of whom were born with albinism, Nomasonto endured taunts and name-calling in the streets and at school.

Albinism refers to the medical condition where people are born without melanin or pigmentation in their skin, hair and eyes. Many of them face health challenges such as impaired vision, sunburn and skin cancer — as well as, quite frequently, societal stigma.

Mazibuko refused to allow the jeering or her eyesight to stop her and she achieved top marks in her class, despite not being able to see the blackboard and having to rely soley on her listening skills.

She went on to qualify as a teacher, but struggled to find a job. Eventually her sister, who worked as a principal, offered her a position at Thembalethu Primary School in Zone 10, Meadowlands. When the deputy-principal post became vacant, parents at the school objected to her taking the job, as she was a person living with albinism and her sister held the top post.

“That was the biggest blow: I felt so different, I had taught at the school for 20 years, I could see educated adults who did not understand albinism. I was shattered, I wanted to tell the world what it is,” Mazibuko recalls.

She went into education administration, in the examination section, climbing the rungs within the department’s bureaucracy and at the same time, did a project management course at Wits University.

Mazibuko decided to launch the Soweto Albinism Society in 1992, from her home in the township, and it grew to a national organisation, receiving funding and support from the department of social development.

In 2010, she retired from her career in education and has spoken around the world about albinism, in Kenya and Tanzania, the African Union and the United Nations.

The stigma related to albinism on the continent has led to cases where people have been killed for their body parts to be used in traditional medicines and cures. She has been advocating for people living with albinism to be seen just as ordinary people.

“The situation is much better since I first started; I can see victory ahead. People say albinos don’t die, they are killed for their body parts, perpetrators are in court and they are found out,” Mazibuko says.

She has also juggled her advocacy work with gender rights and is serving her second stint as a gender commissioner, since 2014. “I feel very young,” she says, when asked about her heavy workload.

Mazibuko believes a lot more education is needed at the entry level about people living with albinism and this should be included in the school curriculum and taught to midwives who deliver children born with the condition. She adds that men must learn “it takes two to tango” — both parents can be carriers of the albinism gene.

— Tehillah Niselow

Twitter: @AlbinismSA